By: Wayne Mok

Which rights truly make a person empowered? A society democratic? These are questions that many brilliant minds have grappled with for centuries, if not millennia. There may never be a satisfactory consensus answer to these questions, but it is important to at least consider them, as residents of an ostensibly democratic society, whose founding document names both life and freedom as inalienable rights. The preamble of the Declaration of Independence infamously declares that Life and Liberty are universal rights, and that governments are created between people to secure those rights, deriving their powers from the consent of those governed.

For most Americans, at most times, these two rights do not remain in stark conflict with one another and do not necessitate reconciliation. Rather, they are understood to be complementary. However, since the end of 2019, as a respiratory infection rapidly spread out of China to become a global pandemic, another trend has swept the globe. Publicly marketed as security or public health measures, many governments have arrogated to themselves massive amounts of emergency or reserve powers that they have then used to create shocking change in their societies in stunningly short periods of time.

To be certain, the assumption of emergency or reserve powers are not in and of themselves indicative of a global authoritarian trend. For one, the mere existence of such constitutional clauses or statutes that allow for increased authority of the state during periods of emergency belies their function: they allow governments more tools and options with which to cope with crises during abnormal periods. However, such actions are the classic opening salvo to processes of democratic backsliding. After all, Augustus Caesar himself was never titled Emperor of Rome; he was instead the Princeps, or first citizen. The imperial title ascribed to him describes the reality that all the typically separated powers and authority of the Roman state had been re-agglomerated in his person. This archetypal story has seen parallels in recent events since the spread of COVID-19.

Consider the case of modern Hungary, and its response to COVID-19. Its government, like many, took dramatic steps ostensibly to deal with the Coronavirus pandemic. Like many other governing bodies, it understood that the congregation of large groups was inadvisable during a respiratory pandemic, and proactively sought to maintain continuity of rule. Thus far, not unusual; the United States House of Representatives approved rules for similar ends in the beginning of the pandemic. In March of 2020, Hungary’s parliament voted to allow the Prime Minister, Victor Orban to rule indefinitely by decree. Already worrisome, but the concentration of authority into one man allowed for far swifter persecution of transgender people, and regulate civil society cultural institutions. These are actions that have little if anything to do with fighting the COVID pandemic.

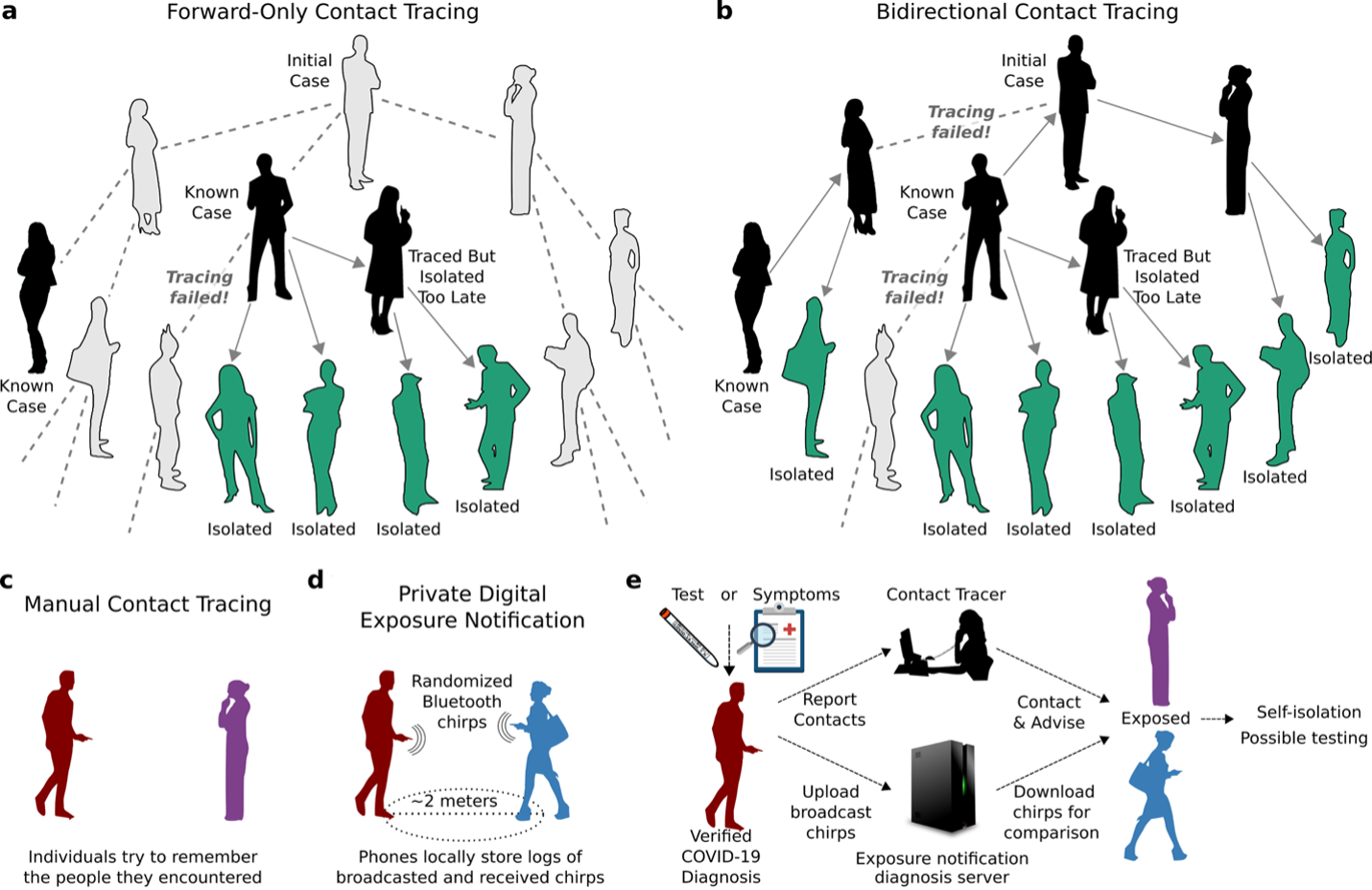

Beyond Europe, Korea has dramatically expanded the use of surveillance technologies in order to trace possible infection between contacts. Such close surveillance and data could easily be abused however, and in a young democracy such as Korea, this is worrisome. Even if many of legal structures to regulate the government exist, such societies may not yet have as concrete norms about democracy and citizens’ relationship with their government that further incentivizes governmental restraint in democratic societies. Such technology is easily abused and can be turned against vulnerable minority populations very quickly- such is the case in neighboring China, where the entirety of the Xinjiang region and its native Uighur population is under 24/7 surveillance, and privacy is a luxurious idea, not an inalienable right.

Even so, this is not to say that nations with an older democratic tradition are not prone to similar tendencies. Australia is for example by all instances a wealthy, Western democratic state. And yet, for the past 3 years, it has spent more time than not in a state of emergency lockdown. One must wonder; how many freedoms can a society trade away in the name of safety before it is no longer free? Again, with the understanding that such actions are predicated on data showing a need for such action, such dramatic mandates are not necessarily undemocratic, especially if supported by a majority of the population. However, the zero-sum relation between public safety and personal freedoms during any emergency must REMAIN an emergency only mindset. These emergency powers are set to expire by default in Australia, as they have in Denmark and other European states. However, this will not be the case for many people across the globe, as COVID-19 has been a gift for authoritarianism everywhere. Many of these changes wrought and powers assumed will not be so easily returned even as the COVID-19 pandemic begins to subside. In that sense, people of the world over need to remain vigilant that their governments’ actions remain in service of protecting them, rather than repressing them, for the duration of COVID-19 but even beyond.

0 Comments