When we consider strongmen or populist leaders in Latin America, Nayib Bukele and Evo Morales stand out. Bukele was raised in El Salvador by the children of immigrants and Morales was raised in the Indigenous parts of Bolivia. However, the two would both come out of the woodwork and win massively in elections in both their respective countries. People gravitated toward their ideas as they promised to change to a status quo that many individuals in both countries found untenable.

The result is a change that we have seen in democracies across the globe, populist outsiders enter the political scene and promise to fix the situation. In the case of Morales, he arguably expanded some democratic rights but removed institutional guardrails to do so. The result was his removal in a coup d’etat, and now Bolivia continues to have a tense political environment. In El Salvador Bukele continues to ride the high of his political popularity; in fact, he has won his most recent election with record success. However, much like Morales, Bukele has faced claims of fraud. Whereas these two figures may seem dissimilar, their heavy-handed approaches to governing and lack of regard for the rule of law are strikingly similar.

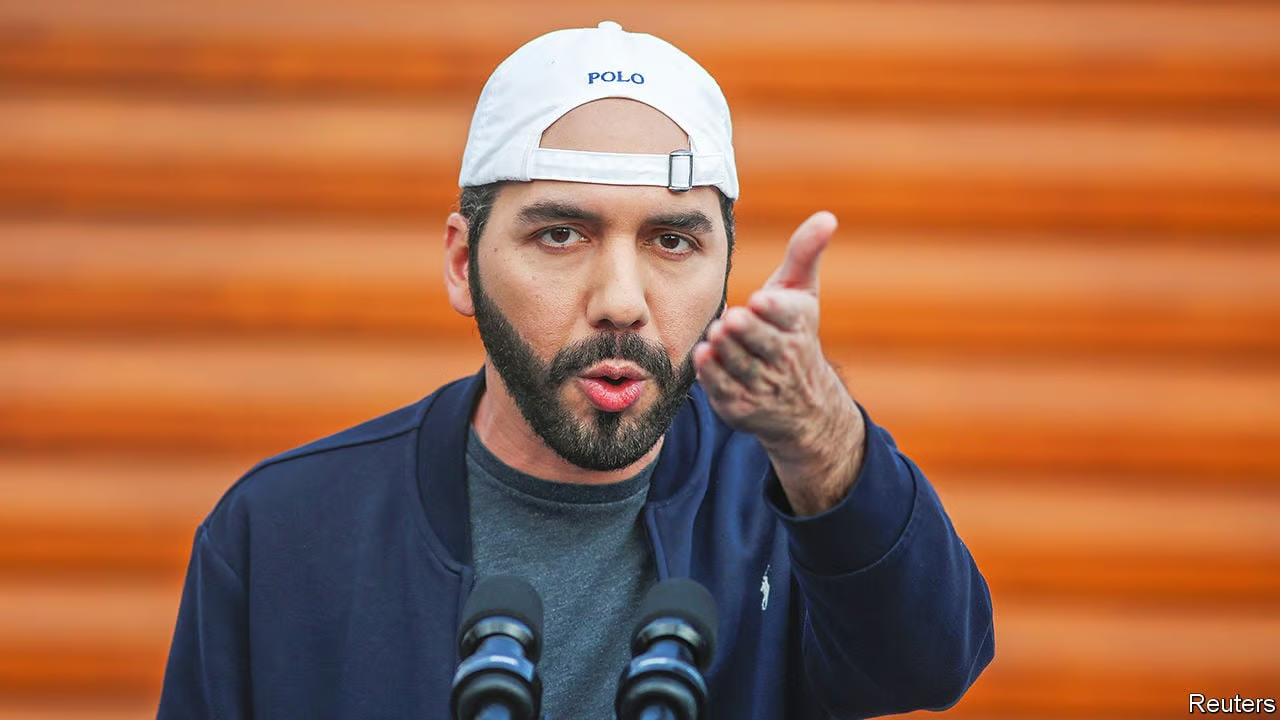

Bukele rose to power in the 2019 Salvadoran election when he and the Grand Alliance for National Unity Party won the presidency. This marked the first time since the Salvadoran Civil war that a candidate not from one of the countries two major parties. In 2020 Bukele started to show authoritarian tendencies when he ordered the national assembly be convened and then sent soldiers into the building. This was under the pretext of trying to pass a 109$ million loan to fund security forces to stop gang activities. This move has been called a coup attempt by the opposition, but supporters have rallied around the move to stop gang violence. The El Salvador Supreme Court weighed in on this situation and ordered Bukele to refrain from using the military in ways that “endanger the republican, democratic and representative system of government.” However, this would not be the last time he would attempt what some would call a coup as in 2021 he used his supermajority in congress to replace the country’s top judges and attorney general. This looks especially dangerous considering the Supreme Court is what provided oversight during the last crisis.

The other controversial aspect of Bukele’s policies are the mass arbitrary detentions undertaken by his government to stop gang violence. There have been over 75,100 alleged gang members who have been locked up since the start of the crackdown. This crackdown has been criticized by the Office of the United Nation High Commissioner for Human Rights and on the other hand has had other countries in Latin America calling for similar policies to be implemented in their own countries.

Another populist leader, Evo Morales, came from humble beginnings and was born into an indigenous family. He rose to power through unions and then with the election of his party, Movement toward Socialism (MAS). During his time in office, he nationalized businesses and expanded the political capability of previously disenfranchised groups, such as indigenous people. However, he also removed institutional controls on his position, leaving challenges to his power to come from social mobilization. It is almost universally accepted that better standards of living and more democracy are beneficial, however democracy was expanded in some areas at the cost of other aspects. The power of the media was curtailed under his rule, as well as implementing a new constitution by side stepping congress. After what was deemed by the Organization of American states to be a fraudulent election, Morales was removed from office and de facto exiled from the country.

What Morales and Bukele have in common is that they were both men who sought to further centralize the power of their executive office and defy institutions that stand in their way. The trouble that remains for analyzing these men is that is difficult to assess the damage until it is too late to fix the problem. The issue with subverting democracy to fix issues is that it leaves a country open to a less friendly ruler in the future who may not have the people’s interest at heart. Additionally, there is no practical substitute for horizontal accountability. A key factor in preserving democracy is that institutions are strong and can resist against people trying to undermine them. In both of these cases, the institutions are being set up to fail.

Both Morales and Bukele were elected as people thought they would bring radical change. The issue with this radical change is that both seem to have little respect for institutional guardrails that protect citizens from overreach. They have sought to make grand changes through unconventional means, and the result is that even though these leaders may have the best interest of the people at heart, those who come after them may not share that same respect. What brought Morales down was a fraudulent election, and after Bukele’s recent unprecedent electoral success, there have been questions raised about fraud. The path these men tow is one between populism and upsetting institutional norms. However, the question continues to remain if they truly care about their citizens, or are just vying to keep themselves in power, no matter the long-term consequences.

The selection of cases here is very interesting. While their similarities are apparent from populism to the undermining of democratic institutions and horizontal accountability, I think future insightful commentaries can come from examining the differences they showed and the political outcomes these can result in. Morales banked on relatively genuine grassroots political participation his party took years to organize, while Bukele demonstrated tactics more reminiscent of typical populist authoritarians such as scapegoating (in his case on crime). Will such difference from Morales ultimately result in a different political outcome for the Bukele regime? And depending on such outcome, will it be indicative of possible important variables to consider for populist authoritarians and their resiliency? I think such developments are worth keeping an eye on.

Greetings,

Hi Alex, I think you make a really strong point about how both Morales and Bukele sought to expand rights or deliver radical change but did so by weakening the very institutions meant to limit executive power. I found your comparison of the two especially effective because it shows how leaders who appear very different can share the same disregard for horizontal accountability.

What struck me most was your point about it being “difficult to assess the damage until it’s too late.” I agree — once institutional guardrails are eroded, it becomes much easier for future leaders to take advantage, regardless of their intentions. It makes me wonder if voters are consciously accepting this trade-off because of short-term benefits like security or representation, or if they underestimate the long-term risks to democratic stability.