Image Source: Our Brew

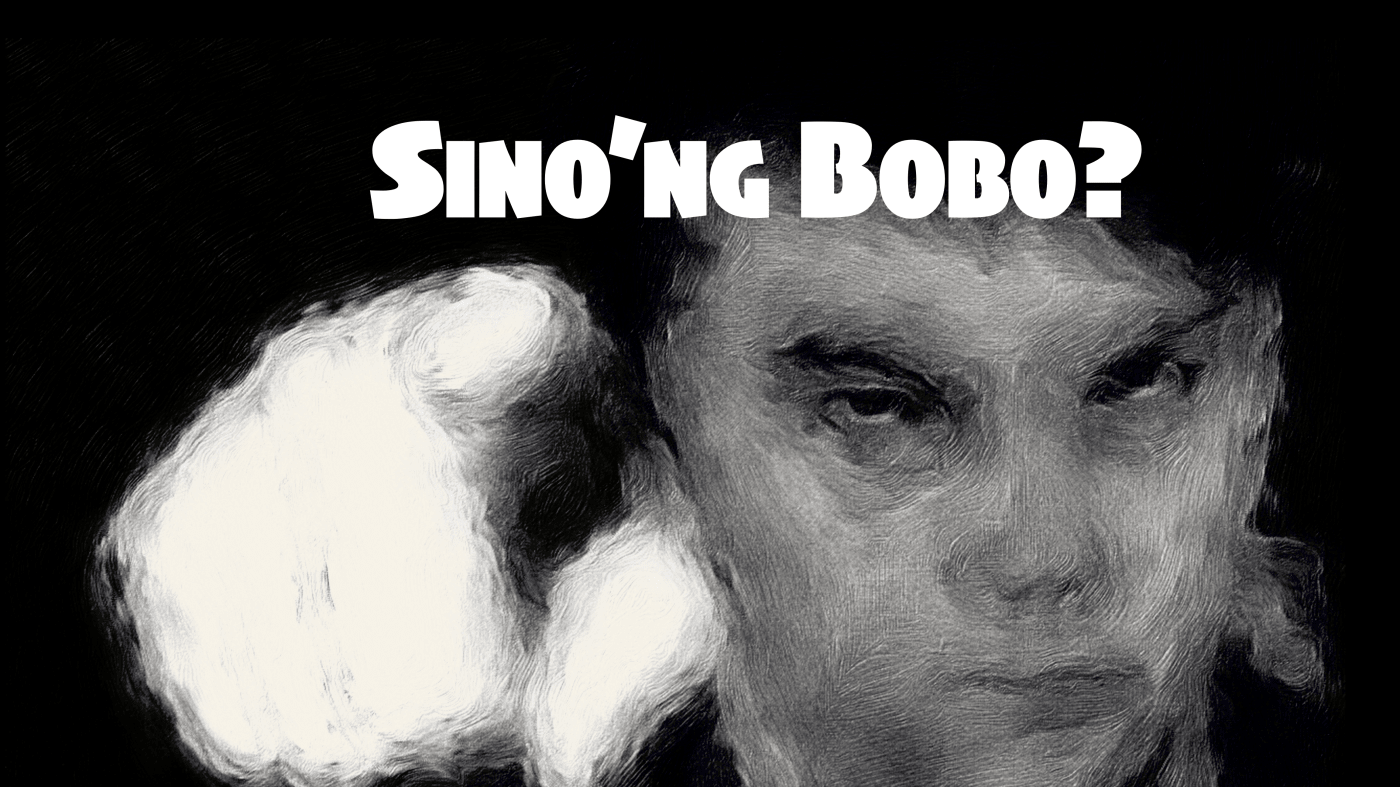

In democratic countries, elections are seen as a great equalizer for each individual, as they are entitled to free expression, regardless of their background. However, this is not the case in the Philippines, as the 2022 election has turned into a battlefield of shame and perpetuated the war of intelligence among voters—further eroding the very foundation of Philippine democracy.

Internal Rift

The term “bobotante” is characterized as someone who impedes the country’s progress due to their presumed unthinking ways of voting, enabling corrupt and incompetent politicians to secure political power. It directs the blame to the poor voters, as they often become targets of manipulation. This argument can be categorized as a powerful form of alienation since it denies or dismisses the voices of poor voters in a democratic process because of the firm belief in the notion of “vote buying.” It reduces the people’s electoral choices to an assumed lack of intelligence, alienating them from participating in political discourse and undermining their roles as active participants in the electoral process.

In the 2022 national election, the Commission on Election (COMELEC) identified it with the highest voter turnout in the long history of the Philippines, with 83%—highlighting the growing political participation and engagement among Filipinos. But in spite of that, this election cycle evidently deepened the existing political divide among Filipino voters due to the resurfacing of narratives that questioned one’s perceived intelligence.

At that time, the “us vs them” mentality was between the supporters of the 2022 presidential candidates: Ferdinand Marcos Jr. and Leni Robredo. Although, in the context of the Philippines, this mentality was further localized in the form of ‘rational’ vs. ‘dumb’ voters. Supporters of Robredo (Kakampinks) are viewed as the ‘rational’ ones, while Marcos supporters (Marcos Apologists) are dismissed as ‘dumb’ voters or ‘bobotante’; otherwise, it goes the other way.

This internal rift among Filipino voters roots in their different stances and views before and after the victory of Bongbong Marcos. For the supporters of the Marcoses, they viewed the victory of Marcos Jr. as another opportunity to experience what they believed was the “golden era” of the Philippines. Meanwhile, for Robredo’s supporters, it was a nightmare, as it reflected the apparent success of historical revisionism, mental gymnastics, and disinformation orchestrated by the dictator’s family to sanitize their name. They saw it as an apparent rejection of so-called “radical love” and “good governance.”

Henceforth, the heart of polarization rooted in elections in the Philippines can be traced back to the voter-shaming narrative, particularly the “bobotante” label, because it reinforces divisions between different groups of voters.

The Politics of Shame and Polarization

The political discourse in the Philippines is reinforced by the politics of shame. It is not just about engaging in conversation over the contested concepts in the field of politics; rather, the discourse expands as a battlefield between the “rational” and “dumb” voters. Instead of engaging in fruitful dialogue to create a meaningful democracy, it is overshadowed by voter outrage. In this case, the supporters of particular politicians, “Kakampinks” and “Marcos Apologists,” resorted to personal attacks and public shaming to delegitimize the personal choice of the opposing side. This form of polarization is a threat to democracy because it undermines and weakens the basic principle and norms of ‘democracy,’ and it fuels authoritarian tendencies to thrive. The reciprocal cycle of shaming does more than assign blame—it distorts the reality of political decision-making because the narrative neglects how weak institutions enable the cycle of manipulation.

The persistent and deepening polarization of the Filipino voters is fueled by different social media platforms. Considering that information is free-flowing on digital platforms, it created a bubble that fed one’s personal biases. In fact, voter shaming is not a new phenomenon in the context of Philippine electoral history; it is a recurring pattern that resurfaces every election. According to Wataru Kusaka, other terms like DDS, Eraptions, and Dilawan are additional labels to shame voters, particularly the marginalized groups, by questioning their morality and rationality. This pattern of voter shaming raises the question: Is the poor vote not a thinking vote?

Is the Poor Vote not a Thinking Vote?

Political scientists challenged the idea of ‘dumb’ voting to address its impact on democratic erosion, particularly in the Philippine context. Research suggests that a poor vote is a thinking vote, as their decisions stem from their life experiences and struggles. Even if it is a process of selling one’s vote, it is still a well-thought-out process guided by reason and logic. These decisions are not random or thoughtless because they reflect the economic hardships and limited opportunities for the poor, which they often see as strategies for survival.

This perspective highlights that voting behavior is also shaped by system inequalities. Electoral outcomes are influenced by weak institutions, political dynasties, poverty, and political patronage. The ‘bobotante’ label only exposes the deep-seated tight class divisions in the Philippines, as it disregards the ability of each voter to reinterpret narratives to make rational choices due to their economic background.

In a democracy, regardless of socio-economic status and educational background, every citizen is entitled to their own voice in shaping the nation’s future. That being said, we can argue that the ‘bobotante’ label is just a mere victim-blaming narrative associated with anti-poor connotations.

Rethinking Our Path Forward

The frustration and outrage of voters over the election results are highly understandable, particularly on the presidential rivalry of Robredo and Marcos—representing “good governance” and “authoritarian nostalgia.” However, our call for an accountable and transparent government should not come at the expense of alienation and exclusion. The ’bobotante’ narrative not only promotes harmful stereotypes, but it also shifts the blame away from the real culprits of our struggles: traditional politicians, weak institutions, disinformation, and poverty.

Rather than attacking the voters who voted for whom, efforts should be directed at fostering a healthier political discourse that acknowledges and empowers the voices of each individual. Let us collectively ensure that regardless of background, every citizen can exercise their rights and obligations as democratic actors. It is now time to debunk the myth of the ‘bobotante’ in Philippine politics and rethink how political decision-making is made; this concept only deepens the divide in our already eroding democracy.

In the following elections, let us focus on strengthening various democratic institutions, as the fate of democracy rests on this, not on the intelligence of each voter. Combating polarization may be difficult, but it is harder to see the continuous deepening divisions in our society without doing anything. It is better late than never. Baby steps, as they say; we can start by respecting every vote, regardless of who casts it. At the end of the day, what we want to achieve is a democratic system where no one is forced to choose between survival and principles.

This was a good read, Kziel!

I agree that the bobotante narrative presents a dangerous trend in Philippine political discourse. Not only does it solidify an us vs. them mentality, but it also perpetuates anti-intellectual narratives that deepen social division and polarization. By labeling voters as either “rational” or “dumb,” it creates formative rifts that fail to capture the complexity of Filipino society. In this case, it divides voters not by ideas but by perceived intelligence. This divide undermines democracy by reducing it to a contest, rather than a healthy competition of perspectives. With these rifts, it brings forth feelings of resentment and distrust between camps.

Moreover, when polarization divides the society into two homogenous camps, it promotes distrust and erodes social capital, creating a sense of otherring, whereas even neighbors begin to distrust one another. This weakens the social fabric and discourages meaningful political dialogue. As Chantal Mouffe argues, the key to democracy is not the absence of differences or the unification of ideas, it needs a healthy competition of ideas. Thus, democracy needs agonism, a respectful contestation of ideas, not antagonism that demonizes the other side. This agonism provides for a healthy democracy where institutions allow political debates, deliberation, and freedom of expression.

In addition, these narratives may be used by some political elites to weaponize the bobotante label, aligning themselves with “aggrieved” voters to gain power. This further entrenches pernicious polarization, as described by Jennifer McCoy, where rival political blocs mobilize through mutual resentment rather than shared vision. This pernicious polarization becomes dangerous as it emboldens these camps to rationalize their feelings of resentment, and be controlled by their emotions rather than deliberate decisions.

Hence, if democracy is to function as the great equalizer, I am with you that we must move beyond narratives of shame. Respecting every vote and fostering spaces for inclusive debate, deliberation, and expression is essential, as every vote matters in this battle that is the elections

Great work, Kziel!

The bobotante narrative is something we often encounter, especially on social media. It’s easy to dismiss voters who don’t support the same candidates we do as bobotantes. By doing so, we also refuse to recognize the nuances and reasons for their voting decisions. I agree that it is counterproductive and problematic because, looking closely, we all want the same things — good governance, better welfare services, and ultimately, good leaders who will put the people’s interests before their own. Reducing rational votes to thoughtless decisions reinforces and deepens polarization, putting our democracy at great risk. It waters down the discourse on why people vote the way they do, and instead, assumes that they do not think when they do. Furthermore, I also agree that the voter-shaming narrative shifts the blame from those who we should actually hold accountable. Voter-blaming only exacerbates disinformation campaigns and allows traditional politicians to gain more support.

To debunk the myth of the bobotante, creating space and fostering healthy discourse is paramount. Understanding the complexities behind every vote will show that what we want from our government is more similar than we think. Hence, to protect our democracy, we must refrain from reinforcing the Bobotante narrative and instead, empower people through empathetic and inclusive discussions.

This is a good work, Kziel!

I like how the work presents a deep analysis of the poor vote as a thinking vote. I agree that even when voters sell out their votes or vote for trapo politicians, these actions are still rooted in their lived experiences. Further voter analysis should follow this frame of thinking from the perspective of the voter.

Personally as someone who has thrown around polarizing terms like “Kakampink” and “Dutertards” both in derogatory means, I understand how this shuts off discourse and just leads the conversation to a battle of ad hominem remarks. This practice should not be tolerated and must be changed as this just furthers the political divide and does not allow parties to meet on middle grounds and understand each other’s stances.

I agree with the path moving forward but I would add that polarization has been given a new context especially with the Marcos-Duterte rift hence a renewed analysis considering this rift must also be set forth.

Hi, Kziel. This was a really nice read. I agree that voter shaming is very prevalent but even more so in the grassroots level. This is particularly the case with people who transmit elitist values. I remember my parents using this exact narrative when we were discussing the 2025 Midterm Elections. My mom, who was well-connected with the people in our neighborhood, expressed her disappointment when she found out that some of our neighbors wanted to vote for candidates like the Tulfos and Willie Revillame. In her mind, they were like uneducated heathens who contribute to societal ills. When we learned that Bam Aquino and Kiko Pangilinan were in the top spots in our voting precinct, she exclaimed, “Hindi naman pala sila bobo (They are not stupid after all).”

I agree with the idea that voter shaming narratives do more harm than good especially given its polarizing nature. It breeds hostilities. It prevents us from attaining an ideal pluralism. Filipinos, especially those in the middle class and higher fail to realize that structures contrain behavior and influence choices. It is dangerous to spew this kind of narrative especially in social media as it only enrages people who view themselves to be marginalized by people above them. Case in point, the people from Mindanao become enraged at their perceived marginalization by people from “Imperial Manila.”

Although this kind of polarizing narrative may be hard to separate ourselves from given our passions for our political beliefs, it is something that we should all strive to be cognizant of so that we can avoid it altogether. I agree that democratic institutions should be reformed moving forward, but I would like to add that a shift in political culture and discursive narratives are necessary to combat this issue.

This was such a nice read, Kziel! It made me ponder on a lot of things.

The term “Bobotante” reflects an inimical view that undermines what we have been fervently fighting for. We truly cannot hope for a progressive government and society if we continue to use derogatory and backward approaches like this. It only deepens the rift among us and further widens the gap between “us” and “them.” Such language provokes aggressive encounters and fosters harmful discourse. Moreover, it pushes people further into their echo chambers, ultimately escalating the already existing polarization.

I agree that regardless of one’s process of rationalizing, every vote was cast with the hope of a better life—because who wouldn’t want that? In the following elections, we really must rethink how we will move forward. Public discourse should no longer be centered on “this is the fact,” but rather on reinforcing the idea that our democratic right entails an obligation to make informed choices. It is also high time that we stop reducing people to labels like DDS, Kakampink, Dilawan, or bobotante. Rather, it is time we start seeing each other as Filipinos fighting for a brighter future.

This is a well-put piece, Kziel!

I agree that the “Bobotante” narrative is often used to label Filipino voters as unintelligent, irrational, or blindly loyal to rival political camps. This framing is harmful and dismissive, especially toward those from lower-income classes.

In fact, the bobotante label often serves to degrade poorer voters economically and socially. On the other hand, wealthy or “intellectual” voters are frequently perceived as arrogant or self-righteous, further deepening the divisions in Philippine society. This was particularly evident during the 2022 presidential election between Marcos supporters and the so-called “Kakampinks.” As someone who took part in house-to-house campaigns for Leni Robredo, I observed how the strategy often involved vilifying the other side, creating the illusion that our camp held a monopoly on truth. This ideological framing of the bobotante ostracizes the opposing camp, promoting exclusion rather than engagement. For some, this becomes a “shortcut” to win and achieve institutional reforms, however, the results proved otherwise.

Furthermore, the bobotante narrative is not exclusive to one political group; it reflects broader behavioral assumptions. Vote-buying, a recurring issue in Philippine elections, is often blamed for the country’s political and economic stagnation relative to its ASEAN neighbors. Those who engage in vote-buying are frequently labeled as casting an “unthinking vote,” reinforcing the elitist belief, especially among higher-income and some middle-class groups, that the poor are incapable of making rational political decisions. Your piece strongly challenges this notion, and I admire that.

As we aim to strengthen our democracy, we must embrace diverse perspectives and foster healthy political discourse. As discussed in class, polarization is a key precursor to democratic erosion. Whether ideological or behavioral, the bobotante narrative only worsens this divide and undermines democratic progress.