In the minds of most Americans, states are indissoluble bodies, bound by ties stronger even than those which bind the Union herself. Even in times where talk of secession has become cheap once again, there’s no talk of carving up the states; to do so carries a taboo even greater than that of removing the ‘United’ from their title. But in the sagebrush dotted hills of eastern Oregon, something else has been brewing. Long considered a prime example of urban-rural polarization, nearly all of Oregon’s political divides run along the Cascadia fault that separates the affluent, urban Willamette Valley from the rural and impoverished East. In the East, there’s perhaps no more offensive slur than ‘Portland;’ in the West, the eastern portions of the state may as well be part of Idaho.

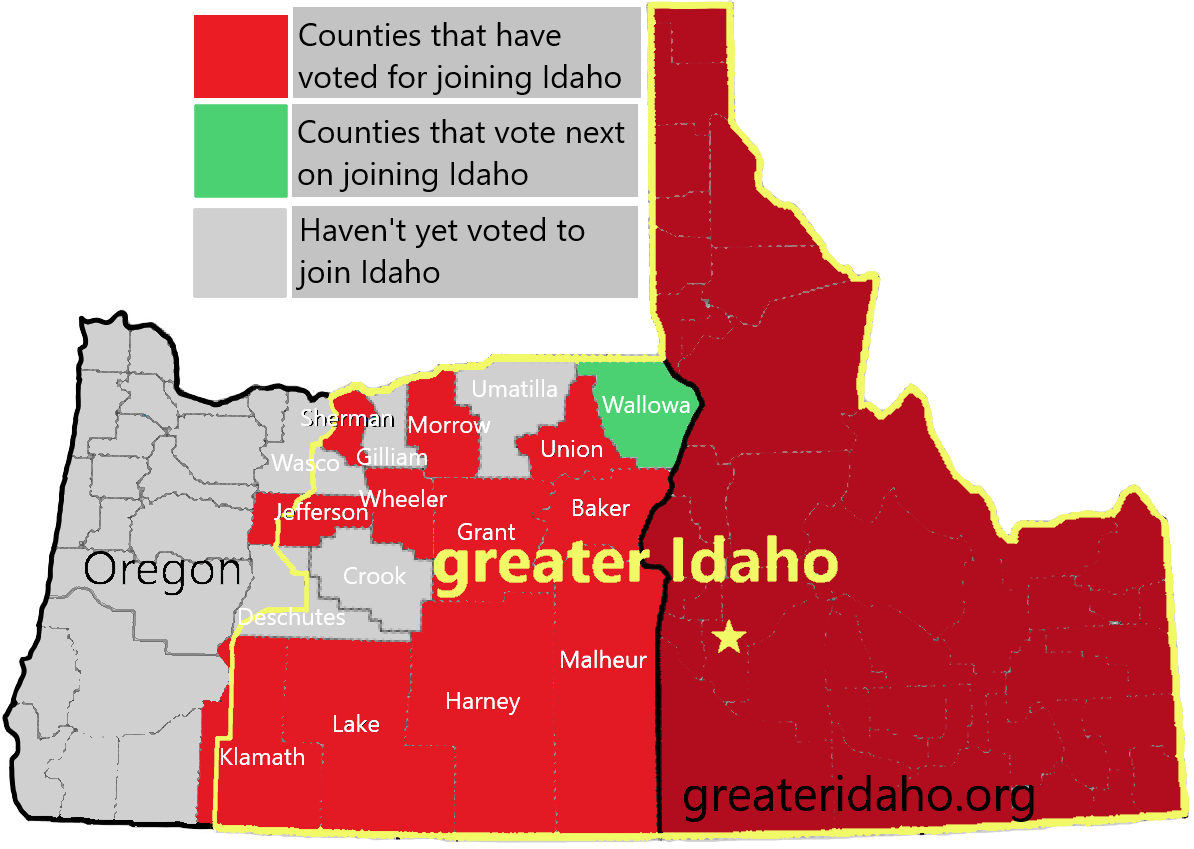

Coincidentally (or perhaps not so), that happens to be exactly what many in Eastern Oregon have been demanding for several years now. The Greater Idaho Movement wants to move Oregon’s border to the Cascade mountains so that people in Eastern Oregon can join a conservative state. Along with advocates in several counties in Northern California and Eastern Washington, conservative activists have circulated annexation petitions in fifteen eastern Oregonian counties. In elections over the last four years, they’ve passed ballot measures in eleven counties expressing their residents’ desire to join the state of Idaho. Even more remarkably, they pushed through a non-binding resolution in the Idaho Legislature calling for the opening of bilateral talks with Oregon over the issue. What was once the subject of bad jokes in Boise bars has become a full-fledged political movement, replete with popular support and a strong organizational structure.

Whether or not Oregon agrees to participate the talks or to the extraordinary demand of ceding nearly three-fifths of her land area, the emergence of the Greater Idaho movement and its manifold successes send a sharp warning to the rest of the nation. Rural Americans are increasingly voting in line with one another as a result of a nascent ‘rural consciousness,’ a group identity primarily based around resentment towards those living in the cities. People living in non-metro areas have come to believe that those living in the cities are less hardworking, less honest, and less virtuous than those in the countryside. As a natural consequence of this belief, many rural people feel as though urbanites (and urban areas as a whole) are granted undue political power and economic resources at the expense of those in the country. This is, in large part, why the cry of ‘Portland, Portland, Portland’ is ever on the lips of Greater Idaho supporters; they feel locked out of power, and as though those living in the cities (including their own elected representatives) are absolutely out of touch with the problems they face.

To be clear, their concerns are not without merit. Although the free trade boom of the 1990s was a boon for many on the coasts, those in the interior were largely left behind. Deindustrialization and the shutdown of domestic extractive industries hit communities like those in Eastern Oregon who relied on logging and agriculture for their livelihoods hard, depressing local economies and diminishing tax bases. In some Eastern Oregonian counties, the average worker makes barely more than half of what a person in Portland can expect to earn. Brain drain is also a serious issue for many rural communities, who have neither the jobs nor educational resources to retain highly educated individuals. In short, rural areas are under-resourced in some key areas, and people living in non-metro areas have legitimate causes for concern with the direction of the state government.

That their issues are legitimate does not detract from the dangers that entrenching political identities along geographic lines present. One of the key drivers of polarization in the modern American political environment is the increasing dearth of ‘cross-cutting affiliations,’ where people of different parties and ideologies interact with one another. As political identity becomes more spatially distributed, there is less opportunity for interaction with those who are not like you. When a person never interacts with those of differing views, and neither do any of their friends, their group identity will become stronger, and the ‘othering’ of different groups will increase. In extreme cases, this phenomenon can lead to a desire for permanent separation of opposing groups, as has occurred in Eastern Oregon. Easterners feel as though they can no longer share a state with those in the Willamette Valley, and are fighting to permanently sever ties. Democracy works best when people with opposing opinions come together to create solutions that work for everyone involved. If we shut ourselves off from one another (with a border shift or otherwise), we simultaneously close the door to compromise, and open a new one to divisive, populist entrepreneurs who will take advantage of our divisions for personal gain.

0 Comments