Co-Authored by Aiselyn Anaya-Hall and John Kaye

Since long before the launch of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the world, and particularly the independent states of the former Soviet Union, have been concerned about invasive and disruptive tactics of a more insidious kind. Russia’s efforts to exert influence over the countries of the former Soviet Union have often relied on stoking narratives of a shared hostile out-group. This group is most often the collective ‘West’, which Russia perceives as motivated by ‘Russophobia’ – an interest to discriminate against Russian-speakers and minimize the global influence of Russia in areas it maintains are part of its traditional sphere of influence. This text will explore the case of the Baltic states with a focus on the Latvian language policy debate and provide background on Russia’s employment of the ‘Russophobia’ narrative to foreign policy aims.

Language policy and Russian influence in the Baltics: the case of Latvia

For the newly independent republics, the dissolution of the Soviet Union ushered in debates not only on the transition to a market economy but also on how states should negotiate language policy between the ‘titular’ languages and formerly dominant Russian (Maksimovtsova & Umland, 2019). When hot-button political issues arise in the Baltics, studies have shown that Russian-speaking segments of local internet communities are used to project Russian narratives and organize anti-western information campaigns, including so-called ‘bots’ spreading disinformation (Dek et al., 2018). While measuring just how effective disinformation campaigns are can be a challenge, in the context of the Baltics research has indicated that sustained information campaigns can influence the behavior of targeted segments of the population (Morkūnas, 2022). Understanding that Russian narratives and disinformation can be effectively spread among local populations makes understanding the information ecosystem a matter of public security.

The language question in the Baltics has become increasingly politicized domestically and the subject of increasing attention from the Russian state. While the experience of the Baltics is distinct from that of Ukraine, the geopolitics of language policy have come to characterize the debate across the post-Soviet space; language allegiances are akin to allegiances in international relations (Maksimovtsova & Umland, 2019). One such controversial and politicized issue of language policy has come to the fore in Latvia, where in response to Russian aggression against Ukraine decision-makers have taken steps to create a stricter migration regime for citizens of Russia and Belarus, requiring non-Latvian citizens in possession of a Russian or Belarusian passport to pass a basic Latvian test or potentially face deportation. Latvian officials have framed migration policy amendments as a national security issue.

Other efforts to modify domestic language policy, including reducing minority language education, have garnered critique as a step too far in Latvia’s ‘decommunization’ process (Nicolas, 2023). On the other hand, the process of de-Russification can be viewed through a post-colonial lens, with some scholars seeing the laws as a form of transitional justice (Snipe, 2023) and factions of Russian-speaking Latvians protesting Russia’s instrumentalization of the Russophobia narrative in Latvialanguage (Postimees, 2023). National identity has been an issue of contention in Latvia since the Soviet period, when a large proportion of urban populations were Russian speaking, oftentimes with limited to no understanding of Latvian. Central to the Latvian state’s integration program after the fall of the USSR was raising the status of Latvian as the state language (as stipulated by the 1922 constitution), also connecting knowledge of the state language to the right to citizenship for those residing in Latvia (Maksimovtsova & Umland, 2019).

Russophobia defined and strategically weaponized

Russophobia is the “excessive animus against the Russian state and its actions, and/or ethnic Russians, that constitutes the belief system of critics of Russia,” (Robinson, 2019). Bias of Russia was largely employed during the Soviet era by other actors because Russia was characterized as anti-West, expansionist, autocratic, and oppressive. Early discourse around Russophobia relied on biases of foreign actors against Russia, outwardly, who still viewed the country as a Soviet Cold War state. Although today Russophobia is a tool in Russia’s political arsenal to advance their political and military motivations.

In the modern era, President Vladmir Putin has redefined Russia as a “state-civilization,” by which Russia’s survival is dependent on its ability to preserve the civilization, i.e., language, religion, culture, and strengthening the state. He believes without a state there can be no civilization and without civilization, there will be no state (Robinson, 2019). Putin used this same “state-civilization” idea to test the level of “Russianness” in another country. Since Russia has defined itself not with physical geographical borders but on cultural ideation, it falsely justifies Putin’s intervention in the Baltic region and concern for the Russian population in the area. If Putin takes further action to invade the Baltics under his political strategy it is to protect the Russian “civilization” therefore preserving the existence of Russia as a state.

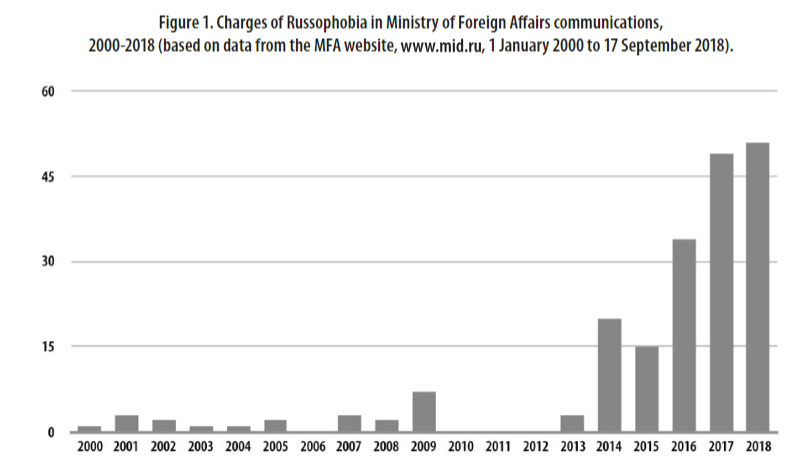

In its propaganda and rhetoric, Russia plays on the Russophobia narrative in the Baltics as the public actively discriminates against ethnic Russians. However, the use of Russophobia as strategic political discourse is relatively new in Russia. During the first half of Putin’s rule, Russophobia was rarely invoked by top officials and the foreign ministry. It was not until 2014 that usage significantly increased. This was a strategic shift in rhetoric to help justify Russia’s annexation efforts in Crimea. Usage of the term rose three times in the communication of the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs between 2014-2015 compared to 2011-2013, see the below graph for details (Robinson, 2019).

*Robinson, N. (2019). Russophobia in official Russian political discourse. De Europa

‘Russophobia’ in Action

The war in Ukraine has created two types of displacements, Ukrainians fleeing the violence of war and Russians fleeing political violence. Many Russians have migrated to the Baltics to circumvent the Russian draft, flee political persecution for opposing the war, and escape economic collapse. In Georgia, one young Russian explained “I was afraid of dying on the front line in this meaningless war” (Mills, 2023). Georgia has seen an increase in its already present Russian population. Of its 3.5 million inhabitants about 100,000 and growing are labeling themselves as Russian. The Georgian people are very aware of Russia’s strategy of upholding a “state-civilization” thus their policies try to limit Russian culture in hopes it would circumvent invasion.

Since the end of the U.S.S.R. Russia has already annexed two Georgian provinces during the Russo-Georgian War of 2008, Abkhazia and South Ossetia (Mills, 2023). As more Russians migrate into Georgia the perceived “Russianness” of the country increases, putting a larger target on Georgia’s back. As a response, however, there are no innocent actors. Georgian efforts to mitigate Russian influence domestically are easily interpreted as ‘Russophobic’. Anti-Russian graffiti lines the city, at bars and cafes signs warn against pro-Putin sentiment, and customers are refused to be served if they order in Russian. ‘Russophobia’ is at a peak in Georgia, but it is more nuanced than just mere hate for the Russian people or traditions. It is in protest of the Russian foreign policy of interventionism. It was Russia’s domineering state civilization strategy that forced Georgia into a protectionist reaction against Russian influence.

Similarly, to the language policy debates in the Baltics, policy and practice perceived as discriminatory against Russians in Georgia may be counterproductive. It is allowing Russia to amplify its rhetoric as an outsider or use Georgia’s prejudice as motivation to intervene and “protect” the interest of ethnic Russians in Georgia. The situation is a double-edged sword, conflict can arise if Russianness explodes in the region, but attempts to subdue Russianness may produce the same result.

Conclusion

Most recently, Latvia’s handling of the Russian-speaking, non-citizen minority through a securitized lens has garnered significant international critique and led to increased accusations of Russophobia from the Russian state. As demonstrated, the language question in the Baltics is far from new. In the case of Latvia, post-Soviet language policy has been a cornerstone of independent nation-building and connected through legislation to a resident’s right to full citizenship. These language policies can be viewed through a post-colonial lens, reinstating the status of the titular language in place of the imperial. Still, national unity and the pervasiveness of Russian narratives may be dependent on the states’ ability to respond to strategic Russian communications aimed at sowing discord between Russian speakers and what it portrays as a ‘hostile West’. The example of Georgia is illustrative of a broader strategic narrative employed by Russia in the states of the former Soviet Union. Striking a balance and creating a strong civic identity will be key parts of maintaining a resilient media ecosystem and society overall.

Sources Cited

Dek, A., Bertolin, G., Kononova, K., Teperik, D., Senkiv, G., 2018. Virtual Russian World in the Baltics. Riga: NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence.

Maksimovtsova, K., & Umland, A. (2019). Language Conflicts in Contemporary Estonia, Latvia, and Ukraine: A Comparative Exploration of Discourses in Post-Soviet Russian-Language Digital Media (Vol. 205). Ibidem Press.

Morkūnas, M. (2022). Russian Disinformation in the Baltics: Does it Really Work? Public Integrity, ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/10999922.2022.2092976

Snipe, A. (2023). Amendments in Immigration Law: What Awaits Russian Citizens Living in Latvia. Eurasia Program, Foreign Policy Research Institute.

Don Mills. (Januray 14, 2023).Russophobia is at its peak. Postmedia Network Inc.

Robinson, N. (2019). Russophobia in official Russian political discourse. De Europa, 2(2). https://doi.org/10.13135/2611-853x/3384

Camut, Nicolas, “UN experts slam Latvia for clamping down on Russian-language minorities”, Politico, February 8 2023, https://www.politico.eu/article/united-nations-experts-latvia-russian-language-minorities/

«Дед, пей таблетки»: в Риге прошел пикет против вмешательства РФ в политику Латвии, Postimees, April 29, 2023, https://rus.postimees.ee/7764556/galereya-ded-pey-tabletki-v-rige-proshel-piket-protiv-vmeshatelstva-rf-v-politiku-latvii

0 Comments